Used by both the good and the bad, and at the same time, they were created for a good purpose but most often used for bad purposes. For some, it would be better if it don't exist, but at the same time it is good that it exists. It reveals the nature of man not in the way we would like to see it. A good example of what happens when the law disappears - not everyone becomes evil, but we know what will happen.

Introduction

The Tor and the Onion Routing are quite interconnected -- mainly because the Tor is a certain implementation of the Onion Routing. When I write about the Onion Routing, I will necessarily also write about the Tor in some sense. I would also like to start with an joke from a certain lecture and say that the name ,,Onion" comes for a reason -- because, like the Ogres, Onion Routing has layers. But let us start with history.

1. History of the Onion Routing, and The Tor Project

Although The Tor Project was founded in 2006, the term "onion routing" was known much earlier, in the mid 1990s.

1.1 Short history of Onion Routing

The "Onion Routing" started in the mid-1990s. The initial work started around 1995 and was financed by the Office of Naval Research. We can call Paul Syverson, Micheal G. Reed and David Goldschlag as some kind of creators of Onion Routing who at that time were employees of the United States Naval Research Laboratory. The project was later developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, patented by the Navy in 1998 and more widely known through the article "Anonymous Connections and Onion Routing," in the IEEE Journal of Communications. This work contained the most detailed specifications of the first generation of Onion Routing. Then work on the project was temporarily suspended due to lack of funds and NRL employees left for other activities. However, the work has not fully stopped. Work on the Onion Routing was fully resumed in 2001 and was financed by DARPA to complete the first generation. Finally, in 2002, the first generation code was abandoned and work started on the second generation called Tor.

1.2 Short history of The Tor Project

The Tor Project started in the last quarter of 2002 and its public version was released about a year later under a free and open software license. In 2004 the project was financed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). In 2006, the research-education nonprofit organization called The Tor Project was founded.

2. Why should I use TOR?

My website that runs on Django collects logs. Let's just look at them:

Command Line

157.158.1##.## - - [29/Dec/2020:23:41:05 +0100] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 301 162 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)...

157.158.1##.## - - [29/Dec/2020:23:41:05 +0100] "GET / HTTP/1.0" 200 7868 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)...

I allowed myself to hide my IP address. I did not display the entire content of the message, but for simple demonstration purposes I would like to point out that when visiting the site using a normal browser we make a direct TCP connection to the server. The server knows who I am, what my address is. A potential third person who intercepts such traffic can easily find out who I am and which server I'm going to. If I don't communicate through encrypted HTTPS this third person can even read my message. Is it a lot? It depends on who is the person who is trying to get their hands on such data -- for potential advertisers it is a lot. If I visit shrek.com, the advertiser definitely knows to include all parts of Shrek released on Blu-Ray in the next advertisement.

2.1 I'm not afraid of personalized ads, that's why I have a VPN/proxy, right?

True, a good VPN will hide your IP address, and allow you to assume the "identity" of a person from any part of the world. We even have an encryption between the computer user and the server via a VPN connection. We also have a slightly lighter wallet, but remember that the VPN providers knows who we are. We don't know if the company we pay to does not register our activity and then sell it further. It often happens that when the police knock on the door of a VPN company's headquarters, it helps with the investigation for the sake of peace and quiet. I do not deny that VPNs are very helpful -- they unlock regionally blocked content. VPNs are fast and secure (they make it difficult to intercept our content). However, the Tor is a bit different piece of bread.

2.2 High anonymity of the Tor

VPN is a centralized service -- there is something that controls and manages it. We have this physical entity here -- a company we have to trust. The Tor is decentralized -- completely independent, no one manages it and no one controls it (although I have to meddle here, because unfortunately, the Tor requires a set of directory servers that centralizes it a bit -- but I'll talk about it later). The nodes are volunteers from around the world. We could say that the Tor is untraceable -- although unfortunately that would not be entirely true. However, it is certainly extremely difficult to track. When using the Tor browser, you never connect directly -- you connect through a random set of on default three nodes that do not know the content of what they are transmitting (except the exit node) and only know their predecessor and successor. The path of this package is quite winding and encrypted. In the end, only the last node can read and execute it -- it has direct contact with the server. Of course, this exit node has no idea who we are and all it does is returning the result. The node that has direct contact with us does not know what is the message.

3 How does Onion Routing work?

As I said before, the Tor -- and specifically the Onion Routing is like <strike>onion</strike> ogres, that is, it has layers.

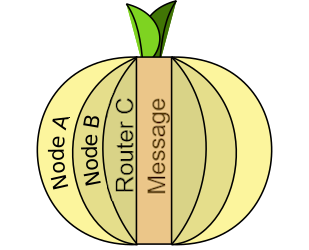

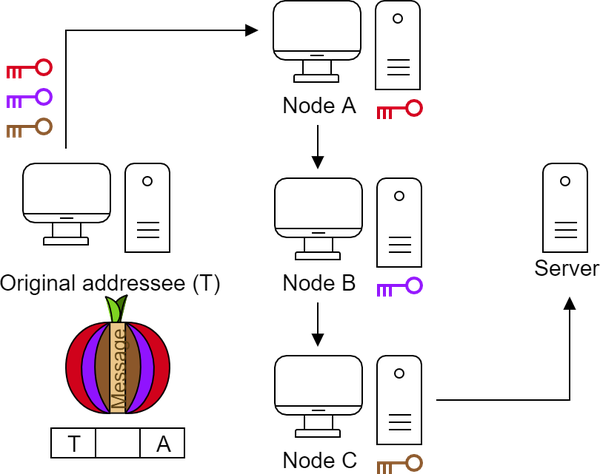

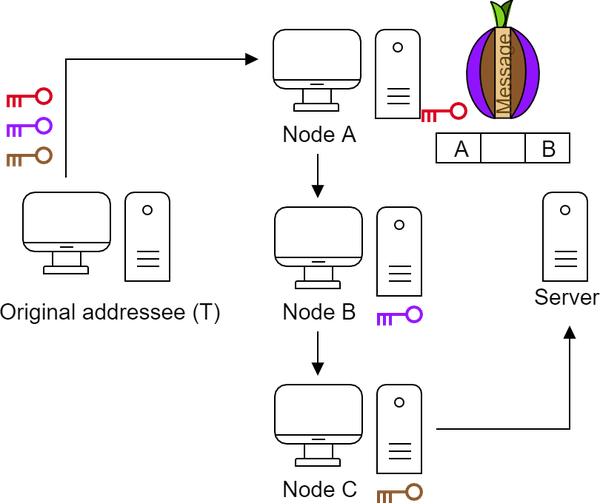

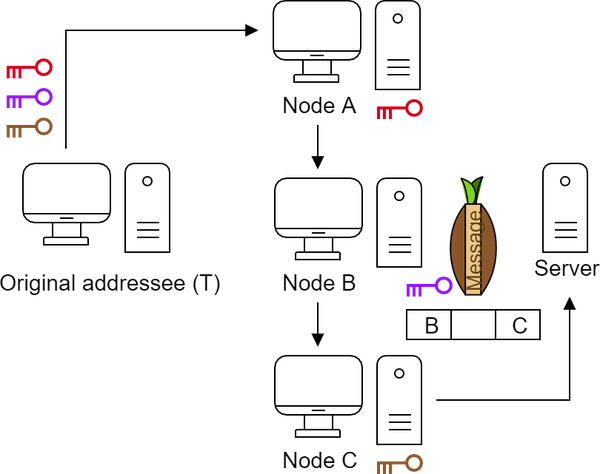

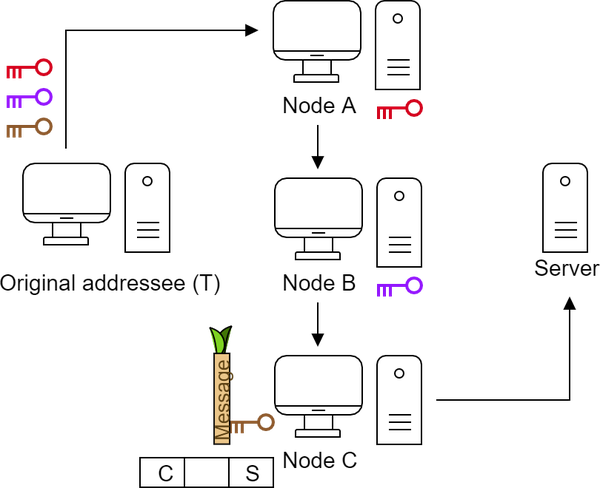

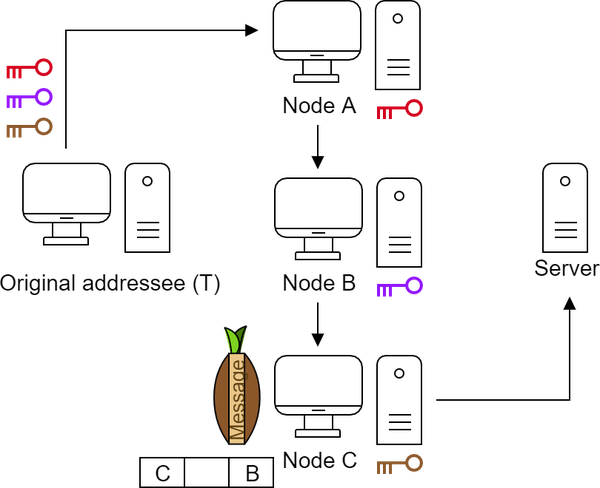

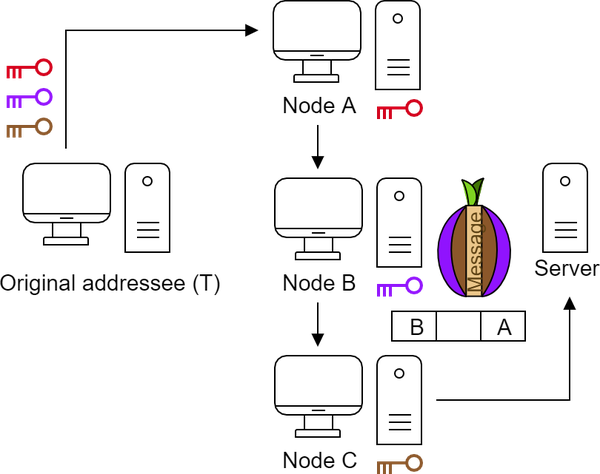

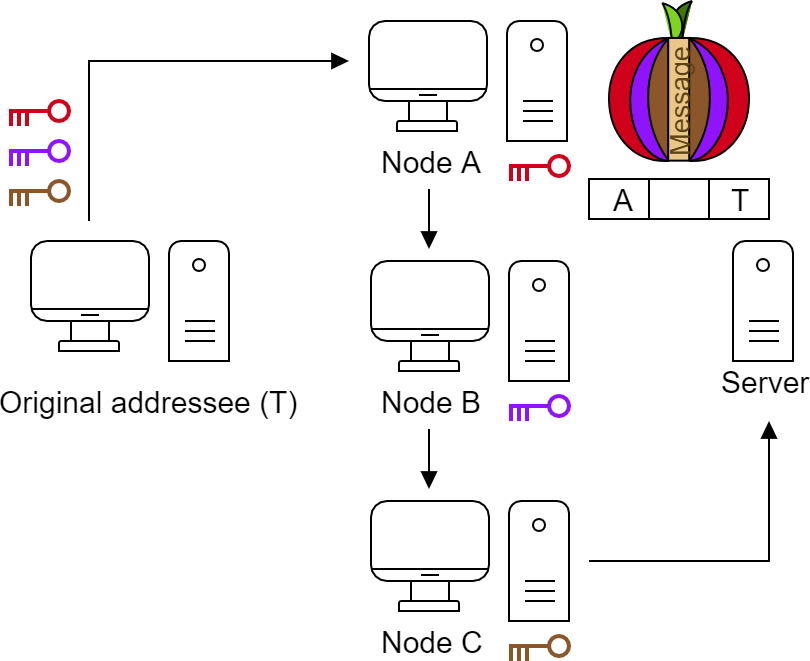

In short, we can imagine it in the way that we wrap our message in successive and successive layers of onions (see Fig. 1). On each layer we write to whom the onion should be given next. We pass this message to the first node (Node A), which rips off one layer of onion and knows from it where it should be handed over next. This goes on until the exit node (Node C) that is able to remove the last layer of onion. Each of these nodes only knows how to take off one layer of onion and only the exit node is able to read the message so it can execute it. Fortunately, it does not know who sent this onion, because it got it from the node that only took off one layer of this onion.

Label: Layers of the onion

Label: The path

Even more interestingly you can imagine it as a closed box. We put our message into the box and lock it with a key. This box is closed to the next box and locked with the next key. We do the same with the third box. Then pass the box to the first node -- although it has only one key and can open the first box where the next box is located and information to whom to pass it. The exchange goes on until the exit node, which has no idea about the original addressee, but by opening the last box it can execute the content and then pass the same way to the intermediary from whom it got the box.

3.1 What do the volunteers (Onion Routers) know?

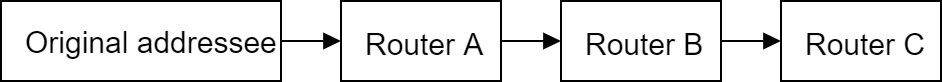

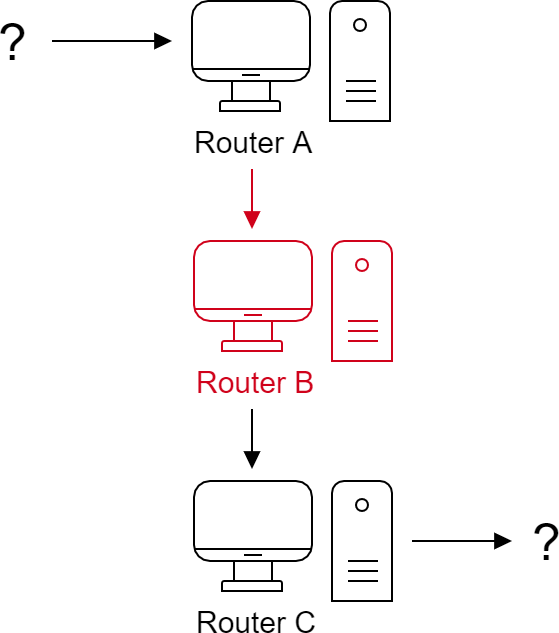

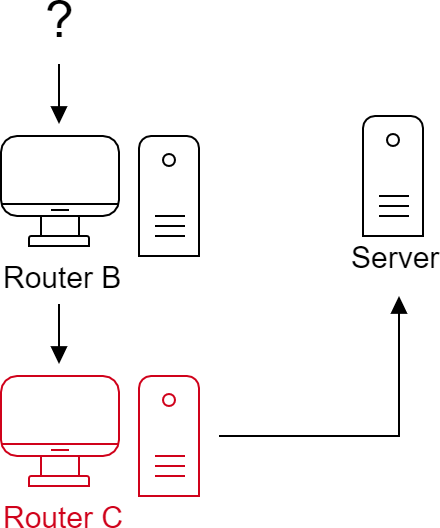

Our volunteers play a big role here -- otherwise known as "Onion Routers", which we will simply call "Router X" (node, or router can be used interchangeably in this case). If they are our direct tool, what do they really know? Imagine such a path:

Label: An exemplary path

Now let's try to imagine what each of our individual intermediaries sees:

What Router A see

The first node knows the addressee, although it has no absolute idea what kind of message it is transmitting and where it will finally arrive.

What Router B see

The B router is in the strangest situation -- it neither knows the sender nor the final destination. It doesn't even know the message content!

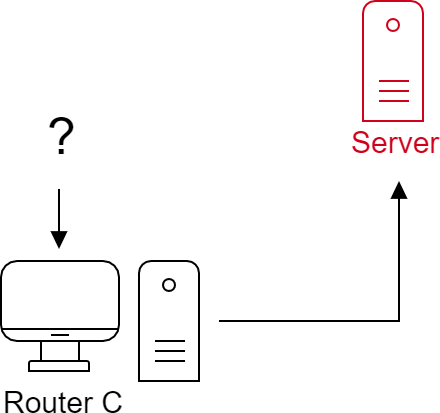

What Router C see

Router C is the only one who knows the content of the message -- but does not know the sender or even the person who had direct contact with the sender.

What Server see

At the very end there is a server that only knows "Router C", but you can quickly find out that it was only an intermediate node in this onion routing. It does not know who originally wanted to make this request. It only returns the result, which returns to this twisty path.

Let us summarize:

- Only the first node knows who the message sender really is -- but it doesn't know what is the final destination of the message or what it contains.

- Nobody knows what the message contains except the last node -- but it doesn't know who sent it.

- No one except the last node knows what the final destination is.

3.2 Number of Hops

I mentioned earlier that the number of nodes (in other words, hops) is on default 3. We can ask ourselves the following question:

Why make connections with only three nodes? Let's use more of them, it will be safer!

The tor is open-source, so YES, we can increase the number of nodes. Will this make the connection more secure? Well... I dare say it will rather be slower. It is, however, hard to say if it will be safer. The length of the path is rather set to three, although it is sometimes longer -- for access to onion services or ".exit" address (.exit was a pseudo-top-level domain that indicate the final node that we want leave the onion network through. For example, we may want the final node to have a Polish IP address.).

So why won't it be safer? If the attacker controls the first and last node of our path, he will still be able to de-anonomize us. This means that even if our path will consist of 100 nodes, the attacker still only needs two nodes -- entry node and exit node. I will say more about this later. However, I would like to draw your attention to the fact that there is a quite interesting mechanism here. Namely, none of these encryption results in changing the size of file. The Tor messages are sent in 512 bytes long cells. It would be too "insidious" if each layer would increase the file size every time. Then it would be easier to determine how many hops occurred. Every message between each node looks like every other message.

3.3 Path encryption

We are rather in a good place to discuss how it all happens. As we already know, each package has a fixed cell size. Now it is worth adding that these cells are unpacked using a symmetrical key. To be more precise, we wrap our message in successive encryption layers -- where there are as many layers as nodes in our path. The message is encrypted using AES, and the key is agreed using Diffie-Hellman.

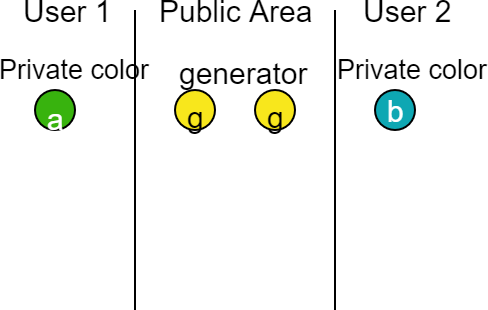

3.3.1 Diffie-Hellman for dummies

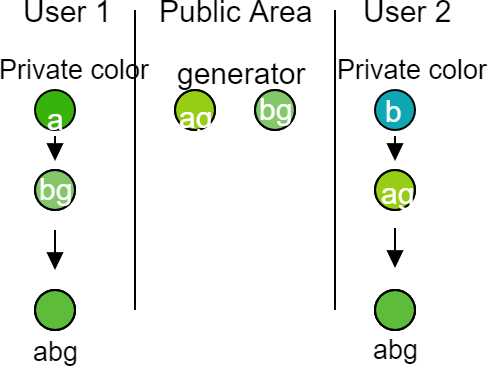

Let's start with a simple example, which is given quite often -- namely a certain exchange of colors. For us, color will be the key. Everything is based on the fact that we exchange some kind of public variables so that both users of them are able to build the same key. It explains everything here rather primitively.

By mixing colors we do not quite know what colors have been used here and it is impossible to reverse this process. Now User 1 mixes his color with the generator (variable g). The same is done by User 2.

After the mixing of colors, a possible third person can only intercept the g generator, and the color ag and bg. Meanwhile, when User 1 and 2 exchange their public colors and mix them again with their private colors, they get a mixture of abg. This mixture is impossible to obtain from the colors available in the public space. You can mix these two public colors, but it will be abgg -- not abg.

In this way, these two users have established a common color -- a key that only they have. The math behind this is much more difficult, but the analogy on colors is quite good.

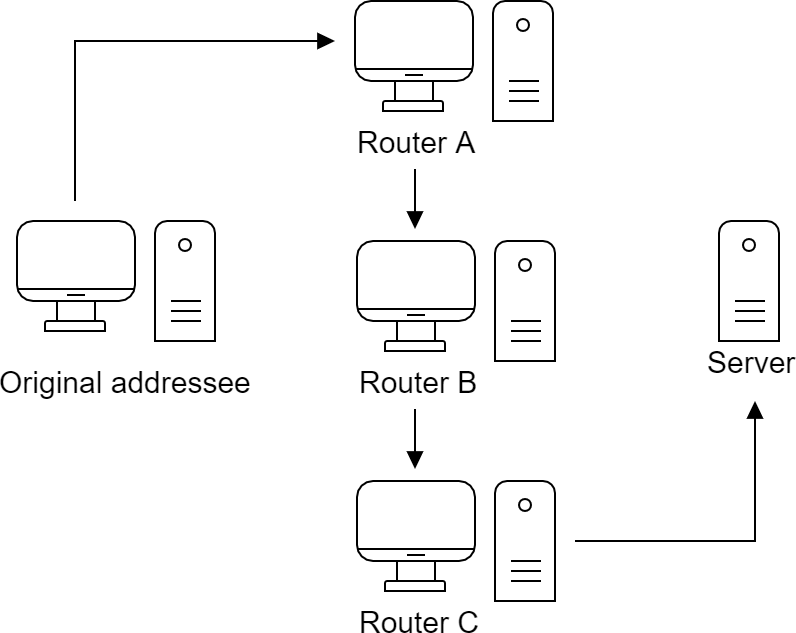

3.4 An exemplary path

Since we already have a little bit more information, let's present once more, a little more detail on how it looks like. The requests (TCP packets) here are a little more simplified -- as we don't need more complex requests in this visualization. I will tell how do we get this path a little bit later -- but now let's take care of the path itself.

After we set the keys with three nodes, we encrypt each layer with these three fixed keys. Next we address this message to the entry node.

The entry node (A) does not know what the message is, but can decode it with its key. Now it knows who is next, so it addresses the package to node B.

Node B also uses its key to remove the next layer. It does not know the content, but it knows who is the next node to pass it on.

Finally, node C (exit node) removes the last layer with its key. It does not know the original sender, but can read the message and execute it.

It encrypts the received result with its own key and returns it to the node that initially give it to it.

Node B does the same thing -- encrypts the message and forwards it.

The last one here is the node A, which returns an encrypted return message, the content of which is still unknown for it. Finally the original sender having all the keys can decode the return message.

3.5 Where do I get this path from?

As I mentioned in 2.2. High anonymity of the Tor, the Tor requires a set of directory servers that centralize it a little bit in some sense. Directory nodes store a list of currently running nodes. At the time of writing this report, there are 9 trusted servers (controlled by different organisations) otherwise known as directory nodes. Directory nodes knows the current state of the network. These directory servers maintain consensus on the state of the network -- make sure that each client has the same information about the nodes building the Tor. It is the nodes that make the directory nodes up to date. The nodes send out information about their status. The directory nodes then compare those with each other and form a consensus based on this.

It is the directory servers where we get our nodes to create the path. The information distributed by the directory servers is signed, and the keys that can verify these signatures are located directly in the Tor software.

3.6 Criteria by which the path is created

I will try to explain here mainly the most important criteria that are taken into account while creating the path:

- <b>In the same path, no node can occur twice.</b>

This would be extremely dangerous, because if this would happen, then there is $\frac{2}{3}$ of the chance (for 3 nodes) that the same node occurs at the beginning and at the end. In this arrangement it knows the content of the message, the final destination and of course the original sender. - <b>We select only one node with the same first 16 bits of IP address</b>

- <b>By default, we select only those nodes that are online and whose configuration is correct</b>

- <b>The first node must be the so-called Guard Node</b>

Guard Node is a kind of special node that has met certain criteria. Such criteria include good bandwidth and high availability. Guard Node does not change very often -- very often after 2 or 3 months. The rest of the nodes change relatively often. Entry Node is a rather dangerous position, since it is the only one who knows the identity of the original sender and that is why additional caution is needed here. - <b>Nodes from the same family are not selected for the same path -- in other words, nodes from the same operator</b>

3.7 The way to block Tor

I would like to mention that not all countries like the Tor network, so they may want to block it. Blocking it is relatively easy -- it is enough to block the source from which a client gets nodes -- Directory Node (or all known Tor Nodes). Blocking is easy, but it is much harder to prevent its use, because the Tor network is then possible to connect by Bridge Node (alternative entry nodes not listed in any public place), whose addresses remain hidden.

3.7.1 Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)

Unfortunately, at this stage the fight continues as many censors use Deep Packet Inspection (DPI). This networking technique allows to analyze packets sent over the network for their content. This may allow the censor to block the connection to the Tor even via bridge. For this purpose Pluggable Transports (PT) is designed to obfuscate traffic so that the censor cannot determine if it is something blocked. This is built into the Tor browser and anyone can use it.

4 The weaknesses of the Tor -- how to de-anonymize

In this section I'll tell a little bit about the mistakes made by people once incompetently using Tor. I'll tell about some ways to de-anonymize Tor users, and about poor solutions in older Tor implementations.

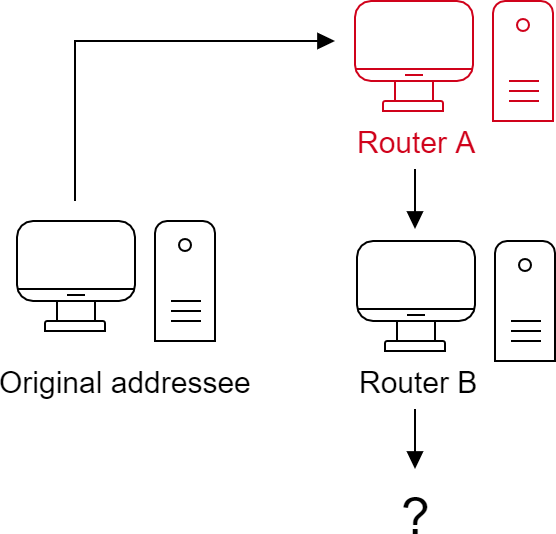

4.1 Analysis of entry/exit nodes

In order to fully de-anonymise the Tor user, we only need two nodes. No matter how long the path is, the number of nodes is irrelevant as long as we get the entry node and the exit node. The entry node will allow us to identify the original sender and the exit node will allow us to know the final destination and the message content. Of course, the Tor is making every effort to ensure that the entry node, or so-called guard node, is reliable and trustworthy. Exit nodes are also selected with caution. Nevertheless, large organizations can still try their nodes to become the guard nodes, and with some luck or other techniques to become an exit node of the path and thus "disarm" network traffic. Large organizations have the funds to create nodes with more than 99% uptime or huge bandwidth -- it can be easy for them to become a guard node and to become an exit node is also not impossible.

4.1.1 Mistake with Directory Nodes

The first versions of Tor contained Directory Nodes, which returned network status based on what they simply saw. There was no consensus here. All potential big company had to do was take over one directory node to share only it's own nodes with the Tor users and de-anonymize traffic.

4.1.2 Confirmation of identity

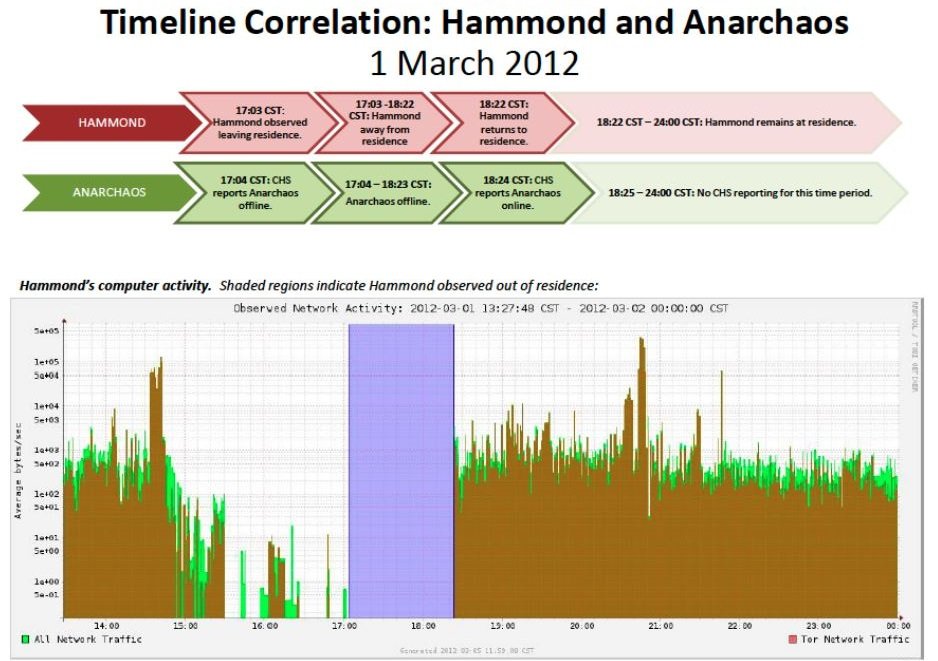

If we are already sure that a certain criminal is the person we are claiming to be, then, just like the FBI did with Jeremy Hammond, we can juxtapose Tor activity with activity in real life. The picture below shows the direction of the packets on Jeremy Hammond's link (obtained by eavesdropping on the link).

Of course, the brown color is the packets listed with the Tor network. The blue rectangle is the moment he left his home. When Jeremy Hammond appeared online was known through one of his friends who cooperated with law enforcement. If such a correlation is close to 100\%, then we rather have irrefutable proof. In alternative scenario that person talking with the suspect could have been an undercover cop who got mixed up in the environment. The interesting thing about in Hammond's case is that a few unrelated facts from his life he shared led to find his person. These were things to be found in the police database, among other things -- and the only person who met all these criteria was Jeremmy Hammond.

4.2 History of Dread Pirate Roberts

How do police can catch the creator of the biggest drug market (and not only) in history? The drug market is located in the Tor network, which is not easy to de-anonymise. Quite simply... look outside the Tor, or wait for mistakes. There is no need for any major technology or eavesdropping on every link.

Ross Ulbricht initially advertised his drug market in many forums under the pseudonym ,,altoid". Many months later, the same ,,altoid" is looking for workers for a job quite similar to a drug market. He published this advertisement with his email address in which his name appeared.

Another mistake he made on the public internet network was a question on the stackoverflow, where he published a problem directly related to his market which he published under his real name.

FBI found a clause in the Silk Road server image saying what IP address is allowed to connect to the administrative interface of the website. The address was assigned to a VPN, and the VPN provider provided the addresses from which the owner was connecting to the VPN, which led to a computer in the internet cafe. At the same time as someone was connecting to the VPN also logged in to a private email address -- we all know to which one.

The public IP address of the Silk Road server has leaked repeatedly. There were many more mistakes and they all show that you don't really have to look for a gap in the Tor itself -- we need to look for mistakes in the behaviour of potential criminals.

4.3 Exemplary technical attack

When one of the major Tor web hosts collapsed, it came back with some javascript code attached on each of the sites hosted on it. The error exploited a vulnerability in the browser that allowed any code to be executed in the context of the browser -- and thus it could save all the activity of an individual user on the infected website in the Tor network as a cookie and send it to a law enforcement server with the public IP address. The error in the browser was quite old (it worked on an older version of the browser), so not many people were caught. This method has also been used before at least once.

4.4 Harvard Bomb Threat

In 2013, during the final exams, a student wanted to delay the exam by sending false threats about the bomb threat. This student used Tor and Guerilla Mail -- but was caught anyway. The main problem was that he was connecting to Tor through the academic network. The Guerilla Mail places the X-Originating-IP header in the place of the email sender.

Command Line

Message-ID: <...>

Date: ...

To: "[email protected]" < [email protected] >

From: < [email protected] >

Subject: ...

X-Originating-IP: [ THE IP ADDRESS HERE ]

Message...

This is where his exit node from the Tor network was written. As all Tor nodes are public, it is easy to determine whether it is Tor or not. So they checked who was using the Tor in the academic network at the time the email was sent. However, he wasn't the only person using the Tor at the time -- which, in fact, wasn't a problem either, because he plead guilty immediately. All in all, there was enough here not to connect directly from the academic network. It is also good not to be the only person using Tor in the monitored network, or it is worth using some VPN.

5 Conclusions

Personally, I think that Tor here is a very accurate and well constructed technology. Let's note that on every of the above examples and on every of the many examples found on the web you can see a certain common part. Namely, the technology does not fail in this aspect, the methods the criminals operated and their poor operations security was a direct problem in their de-anonymisation. Most often they are caught because they allow their information to leak into the public network. Very often it is a bad way of money laundering by the criminals -- and thus misuse of payment systems. Often it is also too much trust in third parties. It happened that the criminals themselves were de-anonymized by meeting the police face-to-face, thinking they were their good friends.

Unfortunately, illegal crime is something I had to mention here and it appears quite often. The technology is wonderfully built and well thought-out, so perfect that it is a good tool for illegal activities. Let's remember, however, that it's not the original purpose, but some bad side of human nature, which appears in many ways -- not only here. Let us remember that this technology is also used by ordinary people who want to remain anonymous.

References

[1] The tor project: Privacy & freedom online. https://www.torproject.org/about/history/.

[2] Onion routing: Brief selected history. https://www.onion-router.net/History.html.

[3] Tor vs vpn: Which should you use and what’s the difference? https://www.comparitech.com/blog/vpn-privacy/tor-vs-vpn/.

[4] How does tor really work? https://skerritt.blog/how-does-tor-really-work/.

[5] How tor works? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gIkzx7-s2RU.

[6] Tor hidden services – computerphile. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lVcbq_a5N9I.

[7] Onion routing – computerphile. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QRYzre4bf7I.

[8] Secret key exchange (diffie-hellman) – computerphile. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NmM9HA2MQGI.

[9] Rolf Jagerman, Wendo Sabée, Laurens Versluis, Martijn de Vos, and J.A. Pouwelse. The fifteen year struggle of decentralizing privacy-enhancing technology. 04 2014.

[10] Why is the first ip address in my relay circuit always the same? https://support.torproject.org/tbb/tbb-2/.

[11] Adam haertle "dilerzy, pedofile, hakerzy..." @ secure 2014. https://youtu.be/hicdX8aQXng.

[12] Def con 22 - adrian crenshaw- dropping docs on darknets: How people got caught. https://youtu.be/eQ2OZKitRwc.

[13] mrphs. Tor blog – breaking through censorship barriers, even when tor is blocked. https://blog.torproject.org/breaking-through-censorship-barriers-even-when-tor-blocked, Aug 2016.

[14] Tor: Pluggable transports. https://2019.www.torproject.org/docs/pluggable-transports.